Authors: Emelly Rusli MPH, Aaron Galaznik MD MBA, Debra Wujcik PhD RN Carevive by HealthCatalystTM, Boston, MA

Background

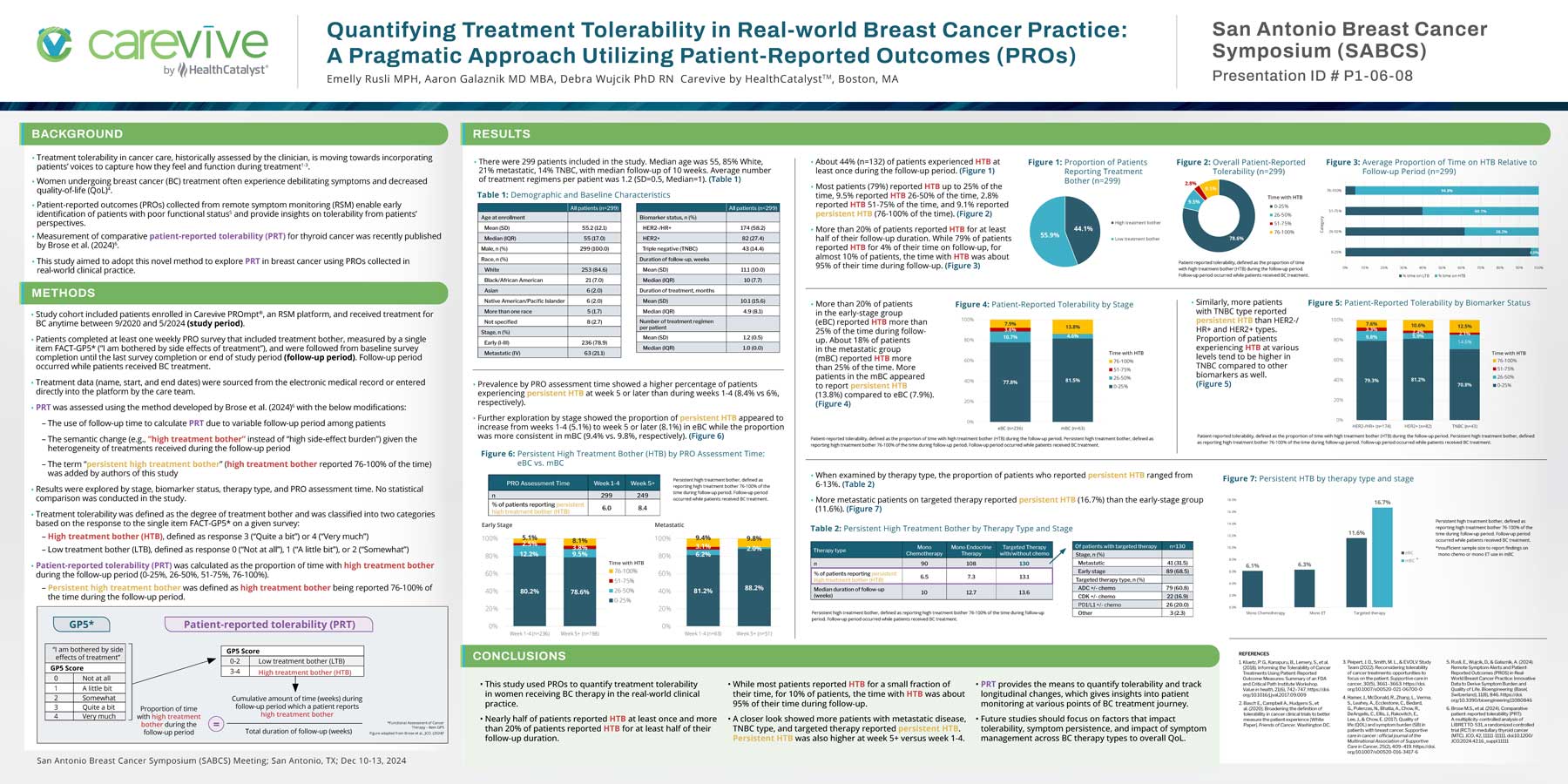

- Treatment tolerability in cancer care, historically assessed by the clinician, is moving towards incorporating patients’ voices to capture how they feel and function during treatment1-3.

- Women undergoing breast cancer (BC) treatment often experience debilitating symptoms and decreased quality-of-life (QoL)4.

- Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) collected from remote symptom monitoring (RSM) enable early identification of patients with poor functional status5 and provide insights on tolerability from patients’ perspectives.

- Measurement of comparative patient-reported tolerability (PRT) for thyroid cancer was recently published by Brose et al. (2024)6.

- This study aimed to adopt this novel method to explore PRT in breast cancer using PROs collected in real-world clinical practice.

Methods

- Study cohort included patients enrolled in Carevive PROmpt®, an RSM platform, and received treatment for BC anytime between 9/2020 and 5/2024 (study period).

- Patients completed at least one weekly PRO survey that included treatment bother, measured by a single item FACT-GP5* (“I am bothered by side effects of treatment”), and were followed from baseline survey completion until the last survey completion or end of study period (follow-up period). Follow-up period occurred while patients received BC treatment.

- Treatment data (name, start, and end dates) were sourced from the electronic medical record or entered directly into the platform by the care team.

- PRT was assessed using the method developed by Brose et al. (2024)6 with the below modifications:

- The use of follow-up time to calculate PRT due to variable follow-up period among patients

- The semantic change (e.g., “high treatment bother” instead of “high side-effect burden”) given the heterogeneity of treatments received during the follow-up period

- The term “persistent high treatment bother” (high treatment bother reported 76-100% of the time) was added by authors of this study

- Results were explored by stage, biomarker status, therapy type, and PRO assessment time. No statistical comparison was conducted in the study.

- Treatment tolerability was defined as the degree of treatment bother and was classified into two categories based on the response to the single item FACT-GP5* on a given survey:

- High treatment bother (HTB), defined as response 3 (“Quite a bit”) or 4 (“Very much”)

- Low treatment bother (LTB), defined as response 0 (“Not at all”), 1 (“A little bit”), or 2 (“Somewhat”)

- Patient-reported tolerability (PRT) was calculated as the proportion of time with high treatment bother during the follow-up period (0-25%, 26-50%, 51-75%, 76-100%).

- Persistent high treatment bother was defined as high treatment bother being reported 76-100% of the time during the follow-up period.

Conclusions

- This study used PROs to quantify treatment tolerability in women receiving BC therapy in the real-world clinical practice.

- Nearly half of patients reported HTB at least once and more than 20% of patients reported HTB for at least half of their follow-up duration.

- While most patients reported HTB for a small fraction of their time, for 10% of patients, the time with HTB was about 95% of their time during follow-up.

- A closer look showed more patients with metastatic disease, TNBC type, and targeted therapy reported persistent HTB. Persistent HTB was also higher at week 5+ versus week 1-4.

- PRT provides the means to quantify tolerability and track longitudinal changes, which gives insights into patient monitoring at various points of BC treatment journey.

- Future studies should focus on factors that impact tolerability, symptom persistence, and impact of symptom management across BC therapy types to overall QoL.

References

1. Kluetz, P. G., Kanapuru, B., Lemery, S., et al. (2018). Informing the Tolerability of Cancer Treatments Using Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Summary of an FDA and Critical Path Institute Workshop. Value in health, 21(6), 742–747. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.09.009

2. Basch E., Campbell A., Hudgens S., et al. (2020). Broadening the definition of tolerability in cancer clinical trials to better measure the patient experience [White Paper]. Friends of Cancer. Washington DC.

3. Peipert, J. D., Smith, M. L., & EVOLV Study Team (2022). Reconsidering tolerability of cancer treatments: opportunities to focus on the patient. Supportive care in cancer, 30(5), 3661–3663. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00520-021-06700-0

4. Hamer, J., McDonald, R., Zhang, L., Verma, S., Leahey, A., Ecclestone, C., Bedard, G., Pulenzas, N., Bhatia, A., Chow, R., DeAngelis, C., Ellis, J., Rakovitch, E., Lee, J., & Chow, E. (2017). Quality of life (QOL) and symptom burden (SB) in patients with breast cancer. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(2), 409–419. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00520-016-3417-6

5. Rusli, E., Wujcik, D., & Galaznik, A. (2024). Remote Symptom Alerts and Patient- Reported Outcomes (PROS) in Real- World Breast Cancer Practice: Innovative Data to Derive Symptom Burden and Quality of Life. Bioengineering (Basel, Switzerland), 11(8), 846. https://doi. org/10.3390/bioengineering11080846

6. Brose M.S., et al. (2024). Comparative patient-reported tolerability (PRT): A multiplicity-controlled analysis of LIBRETTO-531, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in medullary thyroid cancer (MTC). JCO, 42, 11111-11111. doi:10.1200/ JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.11111